In this post we’re going to discuss corset alterations to adjust the fit of your corset, and when it’s worth it to try to go DIY, when to leave it to professionals, and when to cut your losses and just toss (or sell) your corset.

Before I get to that, I will say that if you absolutely hate sewing and you have the funds to commission someone else for alteration or repairs, there is no shame in doing so. Back in 2010 I made a video titled “Should you buy a corset or make one?” where I explained (with math and tables, in all my nerdy goodness) to weigh the pros and cons of purchasing a corset or making one by myself.

But one thing I didn’t factor in was your willingness to learn and how much you value your time. Let’s say it takes ~20 hours to make one good-quality-yet-relatively-simple corset. (This is about right for me, as I’m a very slow and meticulous worker.) If you have no desire to learn how to sew, and you’re lucky enough to have a job where you’re paid over $30 per hour, that means you can work 10 hours and commission a corsetiere to make you a custom corset for $300 (instead of making a corset in 20 hours and saving yourself $300). If you have zero interest in sewing, it’s better to go with the former situation as you’ve just saved yourself 10 hours of labor.

Just as there’s no shame in buying a custom corset if you can afford it (and you simply don’t like sewing), there’s also no shame in sending your corset to a tailor or corsetiere for alterations – nor is there anything wrong with selling your poorly-fitting corset to someone who would fit it better, and buying a new corset that will fit you correctly! Consider your personal situation and use your discretion.

By the way, altering your corset is something you do when your return / exchange period has expired (or if the company you bought your corset from doesn’t have a decent exchange policy). To see the various exchange / return windows of different OTR corset brands, see my page “Can I Waist Train In That Corset?”

With that said, let’s start with fitting issues with your corset, and what can be done about each.

The hips of the corset are too narrow

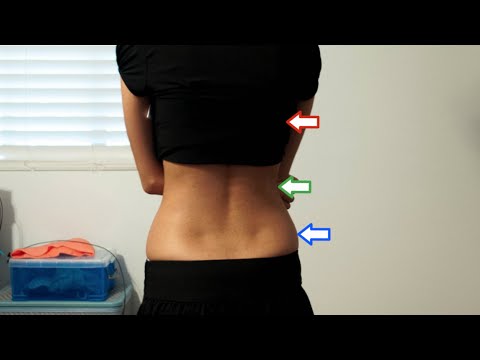

(By the way, this gives the “A” shaped corset gap.) You have a corset that is not curvy enough in the hips, and the solution is to create more space in the hips.

If the corset was constructed using the sandwich method (and only the sandwich method), it’s probably fastest and easiest to add hip ties. The advantage with hip ties is that you can adjust them as you train down your waist – if the waist is loose, you can tighten the hip ties to be snug around your own hips, and as you tighten down the waist, you can loosen up the hip ties to accommodate your own hips as that corseted hip spring gradually becomes larger – so the hips of your corset always fit. With a corset with a fixed hip measurement, there’s a narrow window where it fits best, without being too loose or too tight.

Time needed to add hip ties: 2-4 hours.

If your corset is not made with the sandwich method, or if you don’t like hip ties, you can add hip gores which are easiest to do by slashing the middle of the panel, that way you don’t have to take out the boning and pick out all the seams between the panels.

Time needed to add hip gores: 4-6+ hours depending on the number of gores.

The ribcage of the corset is too small

(By the way, this gives the “V” shaped corset gap.)

Some people asked if “rib ties” are a thing. Technically yes – you can do the same thing on the top half of the corset compared to the bottom half. But generally there’s a bit more pressure on the ribs than there are on the hips, especially if it was a conical rib corset. If you put in rib ties, even in the most straight-ribbed corsets, they will automatically create a cupped-rib corset. Another concern is that over a longer time, those laces would push against your ribcage and that pressure might get uncomfortable over time.

So I would recommend only gores for introducing more room in the bust or ribcage. With gores, you can also control how round or how conical you want the ribcage to be.

Time needed to add “rib gores”: 4-6+ hours depending on the number of gores

If you want to add hand flossing to the gores to strengthen the seams, give yourself extra time for that!

The steels by the grommets are too straight and hurt your back.

This is a pretty easy fix, you don’t even need to get out your seam ripper. You can use your hands to gently curve the steels to fit the curve along your back.

You can also do this in the front, curving the busk itself, or the steel bones adjacent to the busk. It can create a slightly “spoon busk” effect so if you have a protruding tummy, the busk “scoops” it up and in. However if you are very slender (you have a flat tummy with protruding pubic mound), then I might not recommend curving the busk inward, as the bottom of the busk might jab into your pubic bone.

(If your corset contains carbon fiber bones instead of a malleable steel, you don’t have a chance in heck to bend those bones. Don’t even try.)

Time needed to curve the back steels: 10-20 minutes.

The corset is too long (you can’t comfortably sit down in it)

You can cut down the length of a corset, although it’s a more complicated job. My tutorial on cutting down a corset shows how to turn an overbust corset into an underbust (by only cutting down the top edge) but you can also cut down the bottom edge to your desired length.

Cutting down the top edge will stop the corset from pushing up on your bustline, while cutting the bottom edge of the corset will stop the corset from digging into your lap when you sit down.

For a very long corset that’s problematic on both top and bottom, do not attempt to just cut down one edge and “fudge” the fit by changing where you put the waistline of the corset on your body. If you’re tempted to cut corners, you’re better off selling the corset and using the funds towards a better-fitting, shorter corset for yourself.

Cutting down the corset involves removing the binding, removing the bones, cutting down the corset fabric, cutting down the bones (and busk), retipping the bones and putting them back in, and finally sewing on the binding again. See my video tutorial here!

Time needed to cut down your corset: 5+ hours, depending how many bones you need to cut down.

The corset is too short (it’s not fully covering or supporting your lower tummy, and/or may be causing some “muffin top” at the ribs or back)

There are not a lot of effective ways to lengthen a corset. If you are stuck with that corset, then pair it with some shapewear: control top briefs can help pull in and support your lower tummy if the corset stops too high on your hip, or a longline bra can help smooth your ribs and the skin along your back if the corset stops too low on your ribs. But honestly, if at all possible, I would exchange that corset for a longer one – or if an exchange is not possible with your vendor, just sell the corset and use the funds toward a longer, better fitting corset.

The corset is too big or too curvy – can you take in a corset?

Technically it is possible to sew darts or pleats into a corset, but it’s not a good idea because it can create pressure points on the body. I discussed this in my first “Sizing Down in Your Corset” post here.

To “take in” a corset the professional way, where you would never have known it was altered: you would have to apart the corset completely – seam by seam – and cut each panel smaller. But there are so many seams in a corset that it would probably take longer to alter a corset than it takes to make one from scratch. Also, by ripping apart so many seams, it’s possible to damage the fabric beyond repair (and if you don’t have sufficient seam allowance, you’re done for).

You can make a new corset by gutting the last one for parts and reusing the busk and bones, or you can sell your old corset if it’s in good condition and use the funds towards a new, smaller corset.

Time needed to properly “take in” a corset: 20+ hours depending on the complexity, number of panels, etc.

Bonus: you hate the unstiffened, attached modesty panel

Some people hate modesty panels. If you just want to remove your modesty panel, and it’s a standard unstiffened panel of fabric that’s simply sewn into your corset – just take your seam ripper and detach the modesty panel from the rest of the corset. The exception is a WKD corset, where you might have to cut it out instead because it’s sewn right into the lining of the corset and you don’t want to compromise the integrity, the strength of the corset by removing it.

Time needed to remove a modesty panel: 2-5 minutes.

To bone or otherwise stiffen the modesty panel and suspend it on the laces, give yourself an hour. See my tutorial here on how to make a stiffened modesty panel using a sheet of plastic canvas (more affordable and easily accessible than steel bones, and allows the panel to be hand-washed without fear of rusting).

Were there any fitting issues I missed here, or any other fitting alteration tutorials you’d like to see? Let me know in a comment below!